Jesse Detzler

11/5/12

Throughout the history of the world there has always been gender roles. Some have been subtle and others have been not so terribly subtle. Some women have struggled with for years while others have gone unnoticed and unattended to for centuries. One timeless role is that of the Ruined Woman. The woman who has let her morals slip and has thus become something less in the eyes of her society. When a man falls into immoral behavior he can often redeem himself with no great effort. However when a woman loses her morality it is often a greater struggle to regain that which she had earlier cast aside.

This role has been around since the earliest recorded history, and every mythology is full of Ruined Woman. The Bible has Eve, Delilah, the nameless woman who was caught in adultery and brought to Jesus. In Greek mythology Helen of Troy cheats on her husband and cause a war. Approaching modern history we have Shakespeare’s Juliet. This tradition of portraying the Ruined Woman in literary works has continued through the Renaissance, the Victorian era, and into our modern age.

Many different authors in the Victorian Era wrote to display their version of the Ruined Woman, and her affect and role in and on society. One famous writer to do this was Oscar Wilde. An extremely well known Victorian writer and playwright, he authored such works as The Picture of Dorian Gray and The Importance of Being Ernest. He also authored a piece called The Harlot’s House, in which he describes the fallen women and men of his age.

Throughout this piece describes those fallen people in several ways, that are repeated often. In his piece Wilde makes it clear that this scene that he witnesses is a scene of horror and wonder. He speaks of the dancers as shadows and black leaves. Their laughter is described as thin and shrill. Perhaps these words bring to mind haunted woods or dark alley ways. For me this reminds me most pointedly of Washington Irving’s The Legend of Sleepy Hallow. With talk of whiling dust, racing shadows, and leaves in the wind, plus the haunting sound of their laughter puts me directly in the Hallow racing against the Headless Horsemen, trying desperately to cross the bridge that breaks the phantom’s power. This desperate quest to keep my head attached to my shoulders strongly bears a resemblance to the fear that is conjured by Wilde’s description of the Harlot’s House.

Another strong theme in the poem is the comparison of the dancers to things dead, or undead. Wilde calls the dancers ghosts, skeletons and phantoms. This talk of ghosts again puts me in mind of Sleepy Hallow, where many spirits haunt the grounds of the woods. Soldiers dead from war, spies hung by the neck, wraiths desperately seeking redemption from the fate that awaits them. Here this last image is the most powerful. Wilde paints a picture of these sinners as already dead. Perhaps this is an analogy to the difficulty with which these fallen women can reclaim their place in society. They are already dead to society as no one cares about their fate. Or this could be a greater comparison to the fate that awaits them in hell. These sinners, these Ruined Woman, race towards a terrible fate. A fate of damnation and biblically, “but the sons of the reign shall be cast forth to the outer darkness–there shall be the weeping and the gnashing of the teeth.” Matthew 8:12.

A final rhetorical theme present in the poem is the comparison of the dancers to machines. This is what drew me to this poem and made me want to analyze it. As an engineer I will deal heavily with machines and robots throughout my career and hope to be able to see an age when these constructs can more closely mirror human nature. Yet in sense of this poem Wilde paints a much less positive look. Here he describes the dancers as mechanical grotesques, wire-pulled automatons, clockwork puppets, and horrible marionettes. These descriptions are not positive things and when applied to humans are quite terrifying. Not only is this nest of vipers a frightening prospect, with the dancers cast out from society and doomed to a terrible fate, but Wilde seems to be saying that they are no longer even human. So far have they sunk in their sin and disgrace that they are no longer even recognizable as living people, all their humanity lost to lust and greed. This brings to mind the conclusion of George Orwell’s Animal Farm. When the pigs and the humans are suddenly one and the same. Where both the humans have lost their humanity, and the pigs have lost their “animality,” or their nature that makes them similar in appearance and behavior to the other animals. This loss of humanity that Wilde and Orwell betray so well in their pieces is a truly frightening prospect. That the path of sin that the Ruined Women take not only dooms them to be outcasts, with the accompanying threat of hell, but also makes them not even worth attempting to find redeeming features.

Artist Statement

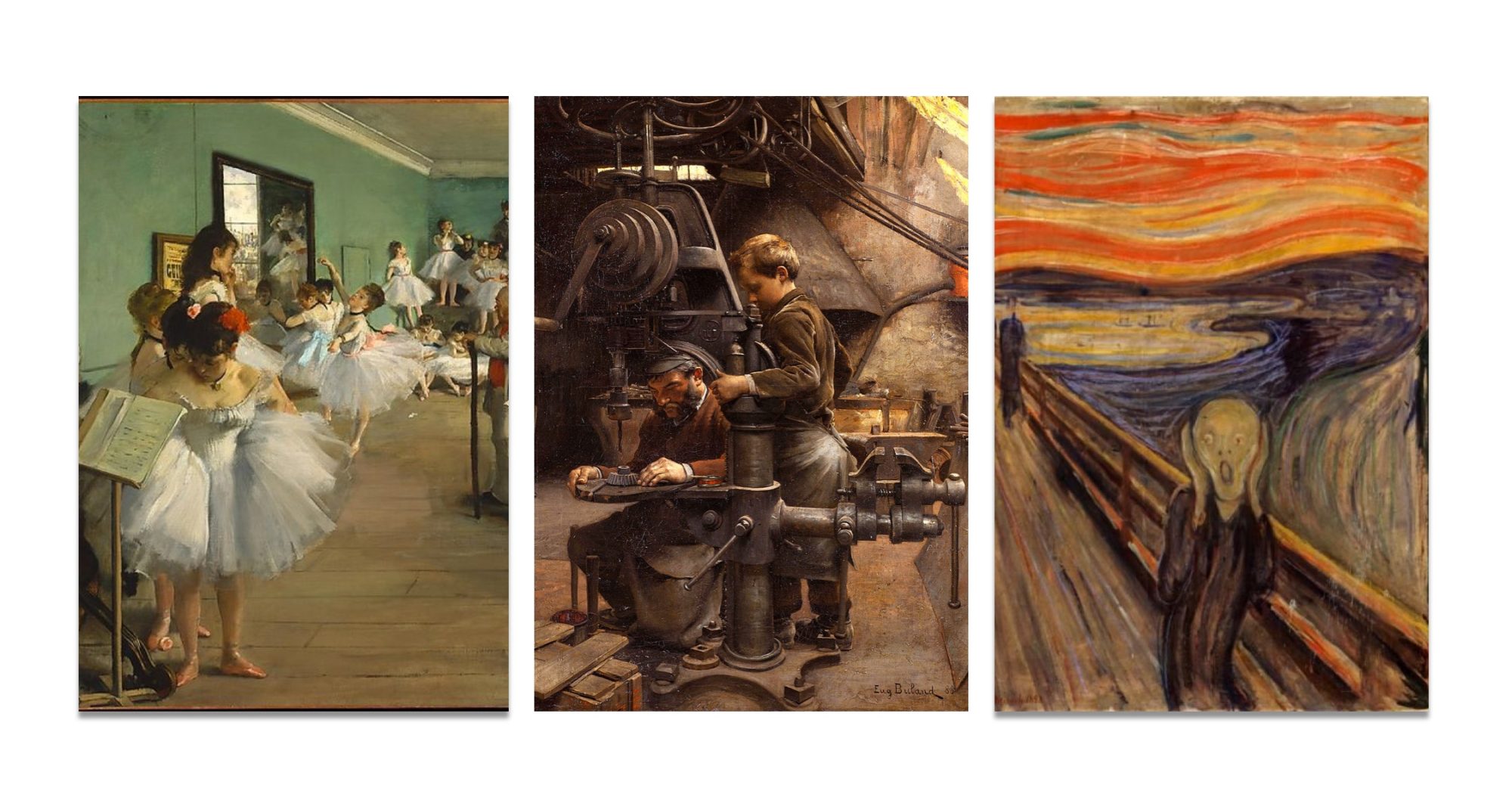

For this piece I was trying to portray the imagery that Oscar Wilde used in his poem. He called the people spirits, shadows, and automations. So I have the people as they envision themselves on the top as beautiful dancers with courtly manner and fancy dress. The men are gentlemen with frock coats and the women are ladies with nice dresses. Reflected in the floor however is what Wilde sees when he gazes upon the dancers. Here they are the grotesques of Wilde’s imagination. The women are marionettes in tawdry dresses with chains on wrists and ankles. The men are but shadows without any real form or bodies. The top is one view. The bottom is another. But which is true? Which is how society sees the dancers? The truth of that may never be known.

A note on the artistic process. The medium is pencil on paper, with some pen thrown if for effect. It should be noted that because my camera didn’t work I had to take several scans of the picture and reassemble it with paint. So it has a much lower quality then I wanted.