Reading through the poem, Jenny, at first I didn’t catch on to the fact that Jenny’s a prostitute and this is essentially a narrator discussing all of the things Jenny’s pitiable for and talking about how she’s tired but fair. We’ve been talking about prostitution so it makes sense that this would be the topic, but the first time I read the poem I wasn’t paying a lot of attention until these two lines demanded it.

“That I’m not drunk or ruffianly

And let you rest upon my knee.”

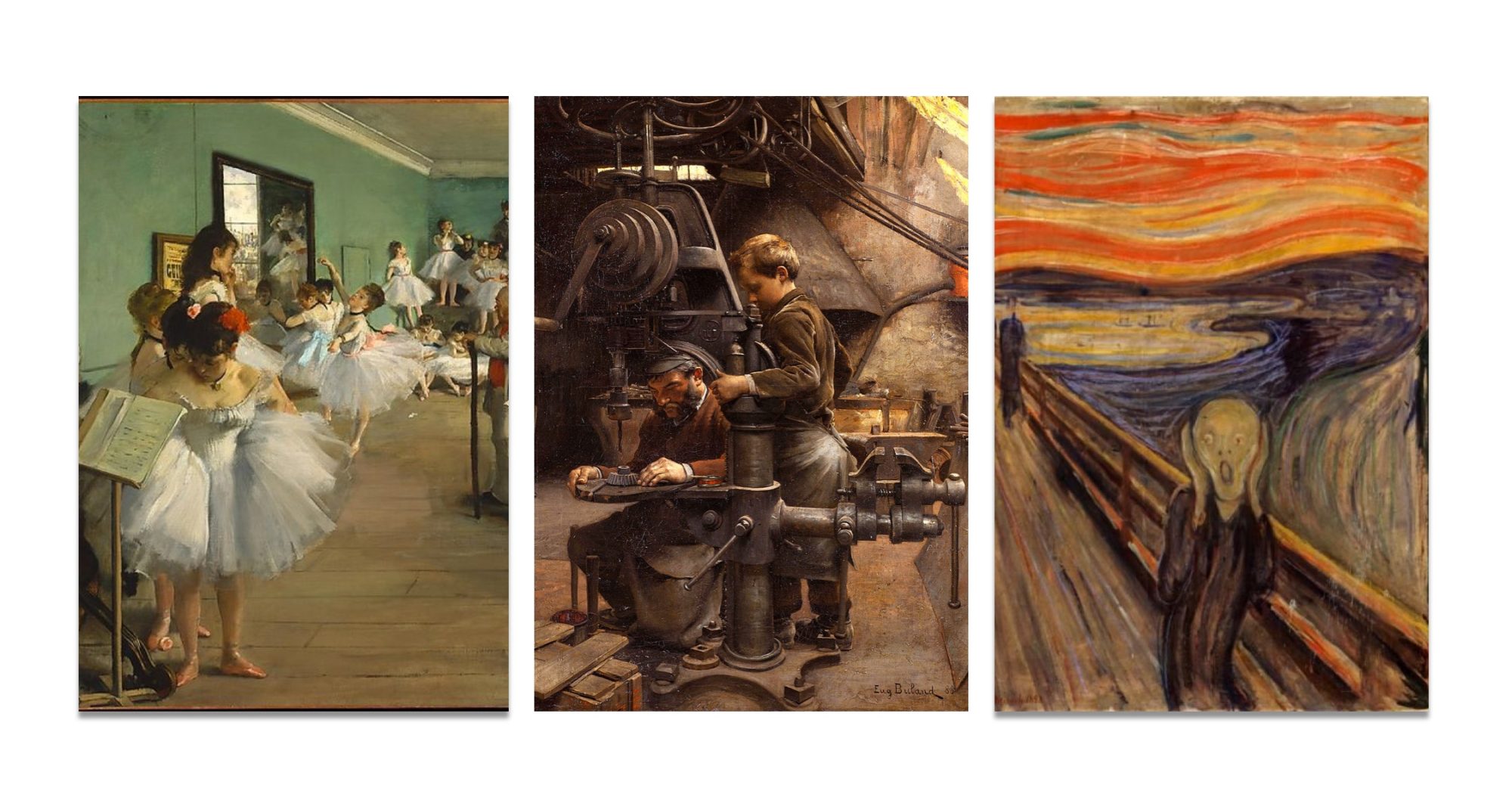

It reminded me of that image of the woman on the lap of the man playing piano, The Awakening Conscience. The very next stanza talks about what we’ve talked about in class. The prostitute has fancy clothes, fair skin, looks healthy. Here, Rossetti shows this by talking about the rest this woman needed and the public shame she experiences.

“For sometimes, were the truth confess’d,

You’re thankful for a little rest, —

Glad from the crush to rest within,

From the heart-sickness and the din…

To schoolmate lesser than himself

Pointing you out, what thing you are: —

Yes, from the daily jeer and jar,

From shame and shame’s outbraving too,

Is rest not sometimes sweet to you? —

But most from the hatefulness of man

Who spares not to end what he began,

Whose acts are ill and his speech ill,

Who, having used you at his will,

Thrusts you aside, as when I dine

I serve the dishes and the wine.”

The whole poem seems sort of contradictory throughout. He keeps mentioning her being tired and worn and needing rest, but also mentions her fair skin, and youth often, almost to keep the reader unsure of whether or not we are supposed to really feel for Jenny.

After reading this and looking at the image, I had to find the rest of the accompanying poem for Found. Both discuss the fallen woman, but in two different ways. Jenny is clearly a prostitute, but the woman subject of Found, seems like a woman who just made a mistake .

“THERE is a budding morrow in midnight: ” –

So sang our Keats, our English nightingale.

And here, as lamps across the bridge turn pale

In London’s smokeless resurrection– light,

Dark breaks to dawn. But o’er the deadly blight

Of love deflowered and sorrow of none avail

Which makes this man gasp and this woman quail,

Can day from darkness ever again take flight?

Ah! gave not these two hearts their mutual pledge,

Under one mantle sheltered ‘neath the hedge

In gloaming courtship? And 0 God! to– day

He only knows he holds her; — but what part

Can life now take? She cries in her locked heart, –

“Leave me — I do not know you — go away!”

Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Ballads and Sonnets, Portland, ME, 1903.

This poem is pretty straightforward, and nice and short. This seems like it’s a drunken one night stand. The lights go out, it’s late, and they get together. In the morning they realize they’re in bed together and they shouldn’t be. The woman panics and tells the guy to get out. Back then she would have been considered a fallen woman, but today it would be just a mistake made in youth.

The poem doesn’t really reflect the feeling one might get from the painting. This woman seems almost a slave. The man finds her and she’s already given up. She’s a slave to her own sin. The man’s face seems almost expressionless, but the woman seems genuinely distraught. Perhaps she’s thrown herself into the street after the possible situation I mentioned above.

Rossetti shows the fallen woman in two ways that are commonly thought of: prostitute, and mistaken woman. It poses the question, could the mistake of the woman in Found lead to the life that Jenny had to live? Found was produced in 1853 or 1859, and Jenny was first written in 1848. Could Rossetti have had the intention to show the fallen woman, and then trace back to how she got there?