Thomas Hardy’s “The Ruined Maid”, is a poem telling a story of rags to riches, tainted with a light only those who understand the idea of ‘ruin’ in Victorian society can see. The poem depicts a dialogue between two women, one who was formerly destitute, the other an acquaintance from that former life. In order to understand the underlying message, it is easiest to break it down bit by bit.

“O ‘MELIA, my dear, this does everything crown!

Who could have supposed I should meet you in Town?

And whence such fair garments, such prosperi-ty?”—

“O didn’t you know I’d been ruined?” said she.

The first maid greets ‘Melia’ fondly, and in such a manner that indicates that they have been apart for quite a while. She is surprised to run into her in town, and that she is adorned in fancy clothes and clearly has come into quite a bit of wealth. Melia replies, “didn’t you know I’d been ruined?” Melia says it in such a way that makes it easy for the reader to imagine her tone of voice as snooty, as if her nose is slightly up-turned. However, she says it as if to be ‘ruined’ is in fact a good thing, despite what most people would associate with the word in other capacities.

“You left us in tatters, without shoes or socks,

Tired of digging potatoes, and spudding up docks;

And now you’ve gay bracelets and bright feathers three!”—

“Yes: that’s how we dress when we’re ruined,” said she.

The maid goes on to describe the previous life they shared- one that consisted of tattered clothes, no shoes, and a life full of manual labor. She takes note of Melia’s new style, which now includes jewelry and exotic accessories like feathers. Melia simply remarks, “that’s how we dress when we’re ruined”, as if that is simply an understood fact.

—”At home in the barton you said ‘thee’ and ‘thou,’

And ‘thik oon,’ and ‘theäs oon,’ and ‘t’other’; but now

Your talking quite fits ‘ee for high compa-ny!”—

“Some polish is gained with one’s ruin,” said she.

The maid goes on to comment how Melia’s speech changed, and now sounds haughty and “for high company”, and Melia makes a remark that highlights the entire sense of hypocrisy of ‘ruin’- “Some polish is gained with one’s ruin”.

—”Your hands were like paws then, your face blue and bleak

But now I’m bewitched by your delicate cheek,

And your little gloves fit as on any la-dy!”—

“We never do work when we’re ruined,” said she.

Melia’s transformation of not only her wardrobe but her entire appearance is evident to the maid, and she points that out she looks like a true lady, not made for hard labor. Melia responds in what can only be imagined as a condescending tone, “We never do work when we’re ruined”. (How nice she makes ruin sound!)

—”You used to call home-life a hag-ridden dream,

And you’d sigh, and you’d sock; but at present you seem

To know not of megrims or melancho-ly!”—

“True. One’s pretty lively when ruined,” said she.

Melia’s old acquaintance recalls the days when Melia was in the fields along side the other working women, complaining about the life she was living. But now that she is ruined, Melia lives a carefree life, which does not have the same sense of drudgery or repetition.

—”I wish I had feathers, a fine sweeping gown,

And a delicate face, and could strut about Town!”—

“My dear—a raw country girl, such as you be,

Cannot quite expect that. You ain’t ruined,” said she. —Westbourne Park Villas (1866)

Finally, the maid expresses her envy for Melia’s improved looks and class status, to which Melia basically tells her is a false dream, as only those who are already ruined can fathom their lifestyle. What stands out in this final sentence is the use of the word “ain’t”. Clearly, this reveals Melia’s humble past, which links her to the farm maid in the only way possible since her decision to cross moral boundaries and become a prostitute.

What that line alone indicates is the sense of close-mindedness that the shift in lifestyle brings. Granted, you may wear jewelry and feathers in your hair, and strut around town like you own the place, but at the end of the day, you are confined by your own narrow sights. Melia throughout the poem clearly has a condescending air about her, indicating that her status as a prostitute is something that she wears proudly, and feels honored to have.

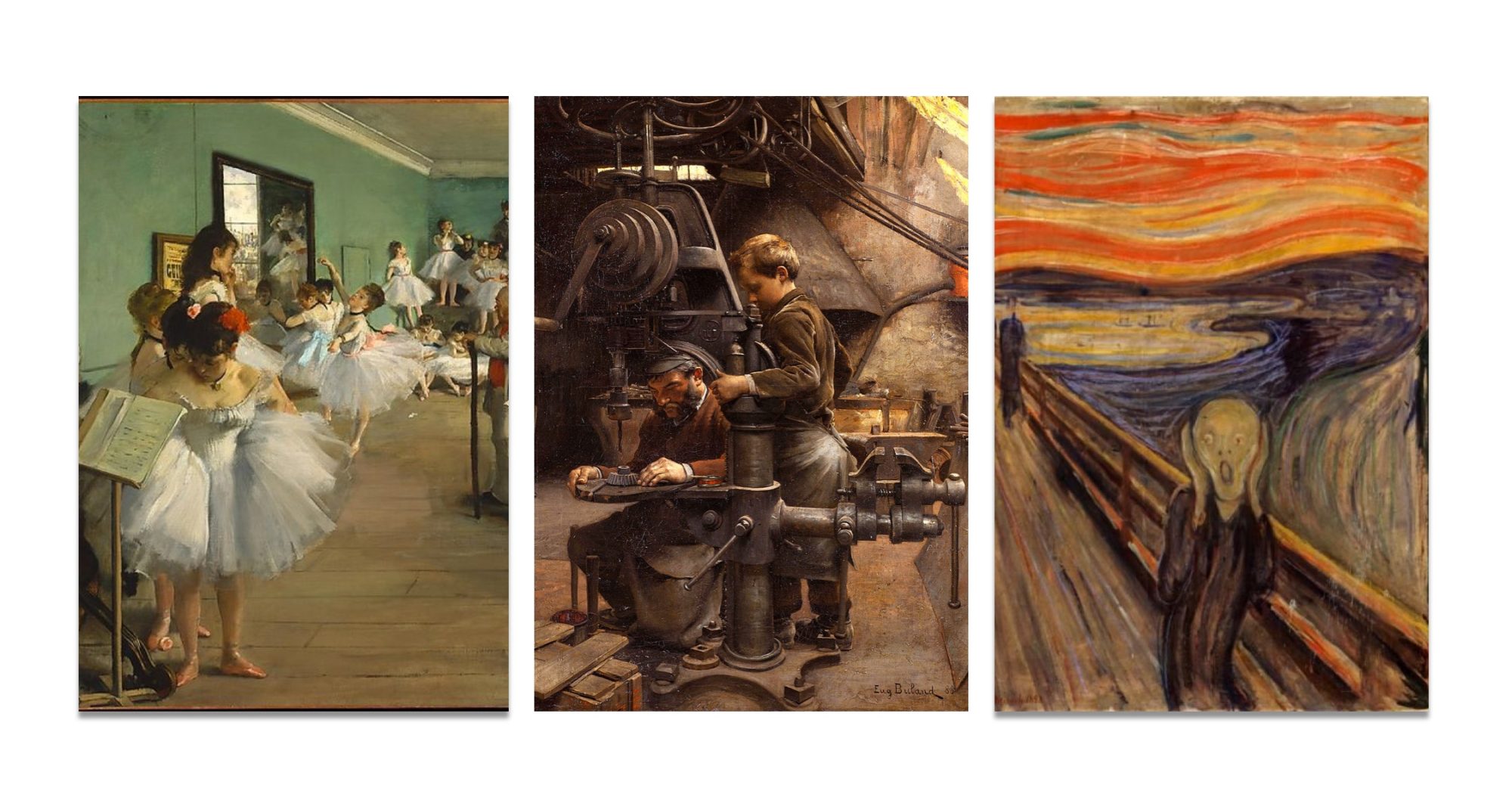

When paired with the sketch entitled “The Great Social Evil”, by John Leech, The Ruined Maid is understood much more clearly. The painting, although from nearly a decade before The Ruined Maid, depicts a similar scene to Melia and the farm maid’s run-in. One woman stands by the door, sporting body language that screams ‘unwelcome’, while another woman (dressed more humbly) faces her. She is holding up her dress which is clearly less grand than the other woman (presumably a prostitute), and is positioned in such a way that hints to a sense of submission. The caption below the sketch reads “Ah! Fanny! How long have you been gay?” Gay, in this sense, does not imply homosexuality, but the status of being a prostitute. While the poem and painting do not intentionally couple up, they do compliment each other well, as they both communicate the sense of reverence and even respect that prostitutes received in Victorian society. It is quite ironic, really, that in a society that is normally perceived as incredibly strict and poised, women often found themselves selling their bodies to live a more enviable lifestyle. While prostitution is almost universally illegal in the United States, one could argue that there are parallels between society’s expectations now. For example, the woman who works 60 hours a week and is paid generously for giving up all her time to her work, is often glorified in our current greed-driven society. While it is not the same thing as selling themselves sexually, can it not be argued that those women in current society looking to improve their lives by dedicating themselves almost completely to their career, are doing so for the same reasons?

We are all taught to want more, to achieve more, and to be the best we can be at whatever it is we choose to do with our life. We seek status, fame, riches, and the “ideal life”, even if that ideal differs slightly from person to person. But at the end of the day, it can be argued that Melia got what we all want- the prestige that comes with sacrifice.