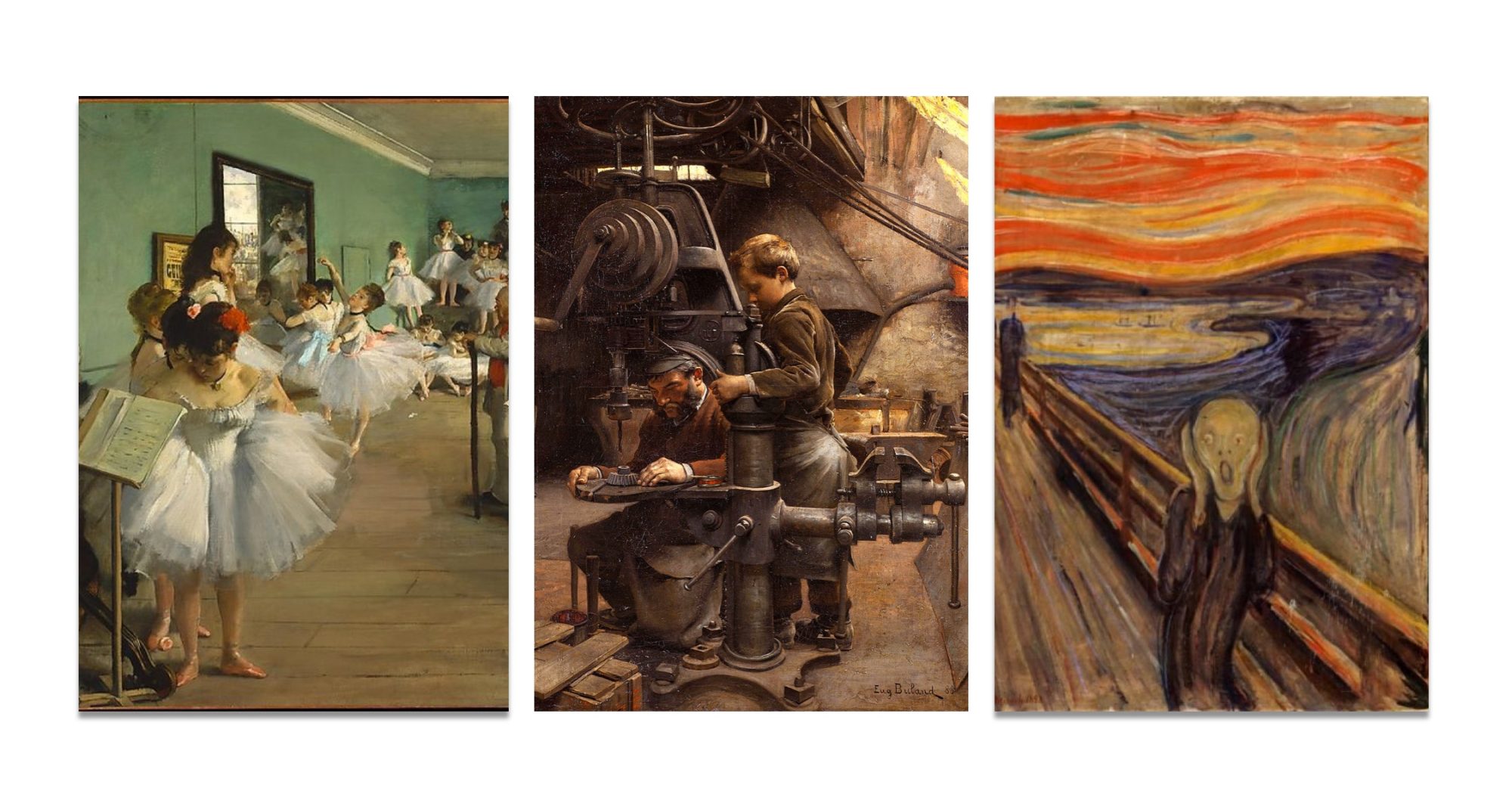

In relation to the ideas and form of Burke’s sublimestate of being and experience, the picture carefully crafted for this critique is initially weak. There is no seemingly ominous terror lurking about them, no feeling of power overwhelms the onlooker. Yet this is probably in its favor considering that it has been done from scratch and therefore invokes an emotion of rugged naturalism; a trait that William Gilpin writes “Should we wish to give it picturesque beauty, we must use the mallet, instead of the chisel: we must beat down one half of it, deface the other, and throw the mutilated members around in heaps” (Gilpin 7). It is this uniquely broken down or “ruined” part of the portrait that makes it inherently picturesque, and accordingly, pleasing to the eye. The light touch that the author conjured within both poems as well produces a palatable entre for the readers’ skimming such clandestine literature.

That said, it should be noted that the ambiguity of poetry is ineluctably attractive because it draws the victim toward a pernicious black-hole of fruitless rumination. The poetry married to the picture is no exception, and further simulates the obscurity facet of Edmund Burke’s sublime. He describes obscurity as “To make anything very terrible, obscurity seems in general to be necessary. When we know the full extent of any danger, when we can accustom our eyes to it, a great deal of the apprehension vanishes” (Burke, 132). Using abstract vernacular and unorthodox syntax the poet has manufactured a jagged landscape of the picturesque in a lyrical mien. Even more so with the drawing, it looks as if the artwork has a bizarre outline prone to oozing off the page whenever its viewers alleviate their daunting gaze. And while at first glance it may fail to produce a deleterious emotion like terror, in time a more experienced observation may lead to an insatiable thirst to know the exact meaning behind it. Similar to J.M.W. Turner’s Snow Storm: Steamboat off a Harbour’s Mouth, the electronically penciled portrait catalyzes the birth of a tremulous atmosphere of danger and darkness, and that of itself produces the sublime offspring called terror. Moving aside from such taboo topics though, in the spectacles of a more personal narrator, I will now refrain from elevated speech as I elaborate upon my life in connection with both the poems and picture.

As a lover of the arts I’ve found that drawing, along with creative writing, is something that seems to flow endlessly out of my mind. Whether it’s striking a blank page a multitude of times until I’ve reached an acceptable frame of what might become my next greatest image, or spending hour upon hour trying to tear a single word from the capacious inventory of the English language, both works of eclectic craftsmanship reveal an unwonted amount of complexity. In a lot of ways this work has been accidentally manufactured into a piece of startling ruggedness that meshes together to make an enjoyable picture. Occasionally, this is how I begin the tedious process of snapping a line, some shades, and every miniscule detail into a congruent and meaningful expression of creativity.

Growing up I was like any kid; bedtime was the alabaster whale of all evils. Sometimes I would stay up reading, other times I would stare up at the effulgent star-covered ceiling till asleep, and on the most restless of nights I would direct an award-winning story. The toy dinosaur would struggle to find its rightful place in a bed-sized world, fighting vigorously to scale the blanket-rolling hills and treacherous cliffsides of the elevated mattress. Time waned on though and soon I forgot the once adventurous tales of reptilian knights, and for a brief period I remained stagnant without any recall of the forlorn bedtime myths I once construed. Yet fate was fain to give me another chance.

I happened to stumble across some blank paper, and as if fortuitously laid before me, I grabbed a transparently orange pencil. An hour or so later I smiled and raised a gloriously scribbled drawing inspired by the muses of old, Jove’s thundering visage reigning down on a helplessly eddying ship. From then on that single picture’s ancestors all consisted of a sea-faring scene filled with monstrous chaos, or the unfortunate explosion of pieces against the jutting jaws of a rapacious coral reef bent on swallowing the despondent spirits. And it is this idea of terror and utter bewilderment that I cheerfully inhale the ineffable descriptions of a seaman’s life and work.

Now before you release a fusillade of comments about how seemingly trivial and puerile this painting looks, allow me to wind back to the initial stage of my drawing (which was so unethically appalling that I’ve decided to refrain from adding it to this essay… and perhaps because I lack the means to as well but I digress). Regardless, having previous history with sketching out sinking vessels, sometimes Kraken-entangled, I began to paste together some rough diagrams. But nothing seemed to work.

So then I decided it best to try drawing once piece at a time, you know, like the mast or poop, or something of that nature. In the end I came very close to pressing out a squiggly caricature of what could have passed for a heap of logs drifting at sea; in a sense, the farthest thing from a picturesque shipwreck. Frustrated, fatigued, and unimaginably famished from a mere thirty minutes of working to flesh out a portrait, I found myself eager to give up. Then a rather painfully sanguine emotion stung me straight on the face like an irksome mosquito determined to draw an opulent amount of liquid victual. I had no possible technique to encode my soon-to-be sublime artwork onto a virtual device. Crushed by the notion I’d wasted several minutes of an evanescent life, I reminded myself heartily that this new obstacle was in fact an incognito blessing. I no longer had to fret over perfecting with the pencil a miraculously intriguing work of art.

Smiling surreptitiously, as if the moment I vouchsafed the petty sliver of pleasure it might crumble to dust with the first sign of zephyr, I clandestinely punched away at the blackened keyboard in search of a viable instrument for my newfangled goal; and there it lay, somnolently piled away like the archaic sagas of Greek legends behind a sundry of useless or otherwise labyrinthine computer applications. I’m sure at this point many individuals will flash a condescending simper and pretend to understand the material value of painting via laptop, but the reality is that few can truly comprehend the intensity of concentration, and the veracity of mental aptitude, that the task of drawing and coloring taxes its lugubrious victim. Perhaps a variegated example is in order so that you can at least somewhat appreciate the fathomless chasm that is electronic brushing.

Day dream, if you please, of the most fantastic and artistically enlightening image that has ever crossed paths with the human eye. Now collide a sledge hammer gracefully into it, throw in some blurred brown and blue and then erase it all until you’re left with naught. That’s how painting on the computer starts, the next part is choosing which brush and what shape to employ. To spare the unnecessary details, after a good hour or two, you may or may not arrive at the picture shown a few paragraphs back. Either way the scene frozen in the screen should suffice. Truthfully, I enjoyed creating the picture even with all its daunting repetitions of having to click, trace, erase, and then start the process all over again. A lingering inquiry may be probing the mind though at this point ascertaining to how exactly my unusual picture does justice to the piously idealistic work of eighteenth and nineteenth century artists. The answer my dear readers is that in every angle it clearly elucidates the realistic drawings of any sublime picture.

Take for example the background of the adroitly crafted object. It neither begs to be blatantly stared at, nor does it proffer to be anything more than the tabula rasa state of being everyone enters this world with. It simply exists much like the ruin of life that, as hauntingly ubiquitous as it is, once accepted as reality brings ineffable peace to the soul. Joseph Campbell had this unwonted belief that the only heaven said to manifest itself coherently was the here and now. Interesting conclusion, but moving on I’d like to present my understanding of the picturesque and all its undeniable, but often hidden beauty; hopefully by donning the elevated habiliment of poetry the idea of sublimeness will become more transparent.

Beauty and Lies

What is beauty? Is it found like the numerals of the ancient Achaeans, or created like the statues of forlorn Europeans?

Can it be bought? Sold? Or perhaps told until naught? Is it the existence of such remarkably pure a design that it courses the length of time?

Then what is beauty if not ugliness? What is a hen other than a crudely feathered swan that the father of Dawn has forgotten to perfect?

Perhaps life is beautiful, or perhaps it is meaningless, nothing more than a jumbled mess. Like the circuitous globs of waxen material that consume a fallen limb, what more is there to this life then a grim, lugubrious ending?

Some would argue there is such a thing as purpose, a driving force that compels us with a righteous impetus to drive out and cleanse this heathen world we so fondly sow into. Yet it is this very course that causes so many spirits to stray away. Serpents may slither silently and secretly shock the sauntering pedestrian, but the silence of a man’s stoical lifestyle causes more suffering than the greatest sin!

So weary not about the particulars, for whatever occurs, shall so sorrowfully suck the sap from a soul that naught matters. And with that one may proceed to journey through life in hopes of finding truth or beauty, but all in vain, for the essence of obtaining truth relies on the reflections of surreptitious lies.

Whiteness

Why does one seek to blot out whiteness? Is there something about that portent which is inevitable Fate that proffers us less? Or maybe one simply prefers to stimulate oneself with the irascible idea that white covered up is no longer white.

So what if it is covered? Does the crescent of a scintillate moon impute that its lunar body has been severed? Of course not! It simply procreates a soporific image that never ceases to seduce us.

Why then does humankind insist on defiling the purity of any and every whiteness? Perhaps because such ambiguity starts a pro-blematic scene within us, how then can we describe white without knowing black? Surely we cannot.

I attest then that such simpleminded mentality prohibits the viewer from under-standing the breadth of its meaning. If we immediately scurry to sketch out a profitable suffix for whiteness then we are left without the sublime sentiment. And if certainly left longing for that feeling, we may find ourselves struggling along the waters of this world starving.

Maybe then the solution starts with a single, humble acquiescence. Hence the answer might be as simple as stopping and sleeping. Not the prodigiously sluggish sort of sleep, but instead the secretly satisfying self-reflection that secretes a sundry of small wonders to us; the kind of slumber that Fate permits a slave to feel sufficiently without sacrifice.

Not bothering to delve too deep within the intricate structure of the previous two poems, I will say that both pose strong questions that may cause some to realize the ultimate picturesque-ness of life. By this I mean that social constructs such as beauty, and debatably truth, are nothing more than what we make them, and this directly connects to the idea of Burke’s sublime because it demonstrates the free, rugged syntax that is trait of only free-verse poems. Although not as beautifully strung together like Mary Robinson’s Ode to Beauty, both writings present a dilemma that I believe was the heart of what many authors and artists alike were attempting to solve. They all wanted to more clearly understand the ultimate truth, and yet in doing so, they realized that such a venture was taking them the opposite direction. In the end, one lesson derived from the heralded composers of words and images may be that in life not everything has to be defined neatly. One day, if possible, humankind may come to understand the essence of our existence, but until then we should continue to struggle determinedly; never losing faith that there may actually be a truth that transcends all others. I believe there is.